PCL Injuries

There are three bones that make up the knee joint – the femur (thigh bone), the tibia (shin bone), and the patella (kneecap). There are two cruciate ligaments—Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) and Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)—inside the knee joint that cross to form an X. The PCL sits in the back of the knee joint, while the ACL sits in the front of the knee joint. Together, they help control the front-to-back motion of the knee, as well as rotation.

The combination of a detailed history, comprehensive physical examination, x-rays, and an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is the key to a successful diagnosis of a PCL injury. Dr. Jorge Chahla and his team use stability tests as part of the physical exam, including the Posterior Drawer test, Supine Internal Rotation (IR) test, quadriceps active tests, and degree of posterior sag to properly diagnose a PCL Injury.

Because isolated PCL injuries are rare, imaging studies, such as an MRI, are important to evaluate the full extent of your injuries.

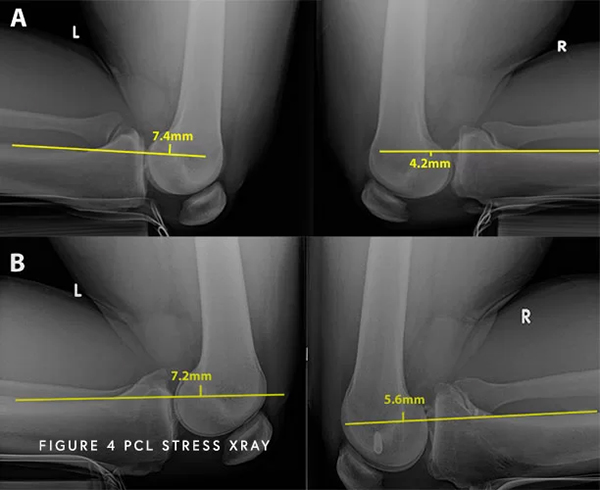

Moreover, an important thing to evaluate is the actual posterior cruciate ligament function. While it can look normal and healthy on MRI after 6 months, it can heal in an elongated position. Although it looks “normal” on MRI, it might not be functioning properly in the knee. Think of a rubber band that has been stretched and subsequently cannot return to its previous tautness. To help determine if this has occurred, one special test that is used to determine the severity of your pathology are kneeling stress x-rays. These special x-rays allow for objective quantification and diagnose (based on validated systems) of a partial, complete, or combined PCL injury with millimeter accuracy. With this information, Dr. Chahla can provide an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan.

PCL injuries can be classified into different types based on the severity and extent of the damage to the PCL fibers. The grading of severity is based on the amount of ligament disruption and the extent of knee instability present following an injury. It is important to accurately diagnose the extent of a PCL injury, as the appropriate treatment plan can vary based off the type of PCL injury that an individual has suffered.

Grade 1 PCL Sprain

This is a small partial tear of the PCL, meaning that the ligament is stretched but not completely torn. The knee may still demonstrate some stability, and conservative treatment such as rest, physical therapy, and bracing can be effective in promoting healing and restoring function.

Grade 2 PCL Sprain

This is a moderate, or near complete tear of the PCL. The ligament may be partially torn, resulting in some instability in the knee joint, although there are some fibers that remain intact. Treatment options may include physical therapy, bracing, and possibly surgery in some cases.

Grade 3 PCL Sprain

This is a complete tear of the PCL in which the ligament is no longer functional. The PCL is fully ruptured, leading to significant instability in the knee joint. Usually, this occurs with injuries to other knee ligaments (most commonly the posterolateral knee structures). Grade 3 PCL tears often require surgical intervention to repair or reconstruct the damaged ligament, followed by rehabilitation and physical therapy to regain knee stability and function.

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is one of the key stabilizers of the knee, preventing excessive backward movement of the shinbone. Injuries to the PCL can result from direct trauma, hyperextension, or sports-related accidents, causing knee pain, swelling, and instability. Dr. Jorge Chahla is a leading expert in treating PCL injuries, offering both non-surgical and surgical treatment options. If you have suffered a PCL injury, schedule a consultation with Dr. Chahla in Chicago, Naperville, or Oak Brook for a thorough evaluation.

At a Glance

Dr. Jorge Chahla

- Triple fellowship-trained sports medicine surgeon

- Performs over 700 surgeries per year

- Associate professor of orthopedic surgery at Rush University

- Learn more